How does an ethnographer check in with a social movement? I spent two

and a half years absorbing the zeitgeist of Los Angeles bike activism

by participating in it. Then I spent two years thinking and writing

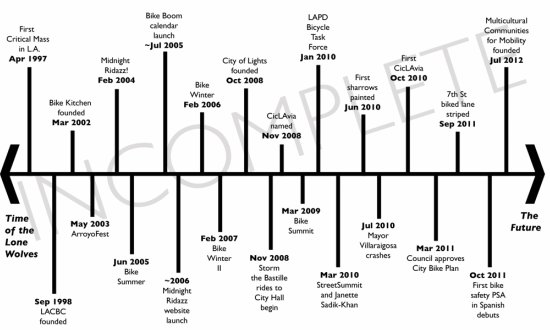

about those experiences. After so much time away from a rapidly changing field site, I've started to wonder how closely the

timeline of bike movement history that I developed aligns with the

narratives of other activists.

On Friday night, Ron Milam and I are co-hosting an attempt at a group ethnography called "Building a Bike Movement in Autopia" (7-9 pm at the L.A. Ecovillage). I wonder how the people who have created a vibrant bike

counterculture in Los Angeles think of their relationship to the

city. Can we, as a group, trace the outlines of the bike movement,

which on its own cannot speak and exists only through the

collaborative actions of multiple individuals? I've learned that

media coverage of community-based movements often leaves out the

complicated webs of human infrastructure that bring subcultural

interests into mainstream reality. People in the street, advocates

taking their concerns to political offices, people who work behind

the scenes in public offices, and elected officials combine in social

networks that affect policy outcomes. This gets glossed over as

"political will" rather than an ongoing process of

transforming popular opinion and policy through visible shifts in how people use space. What do bike activists in L.A. think propelled the

movement forward, and how do they connect that growth with the gains

in bicycle policy seen in LA today?

The L.A. bike movement experiment on Friday is an extension of the

"para-site" concept developed at the Center for Ethnography

at UC Irvine. It is calling upon people who experience/d the changing

state of bikes in L.A. to reflect on their agency. To my mind a

group ethnography extends the participant-observer role to others in

the field, asking interlocutors to become what Douglas Holmes and George Marcus have called "para-ethnographers." When

we're interacting with people as anthropologists, we're hardly the

only ones aware that there is a larger system that give everyday actions

meaning. I want to know what others find significant.

However,

ethnographers also agonize over making representations of what they find in fieldwork, and I don't think creating a collaborative representation of something with multiple participants

like a movement can be anything but tricky business. Activism in a city as

massive and varied as Los Angeles has many layers and milieux.

Who might be left out? For example, choosing the ecovillage as the

location for the event reflects my own embeddedness in the field; I

was an ecovillager during my fieldwork, and it's still my home when I

come to L.A. Because the ecovillage has loomed large in bike

activism, though, it may cast a shadow on the work of others, as a westside

advocate who has accomplished a lot for biking in L.A. pointed out to me.

There's no way

Friday's event can encompass the sheer volume of people and projects

that make biking in L.A. such an exciting world. But maybe with a

group ethnography, incompleteness can be seen for what it is: a starting point rather than

a part masquerading as a whole. My goal for Friday is to create a timeline of important

events and moments in L.A. bike movement history, combining many

individual perspectives into one partial narrative. There's already a

tremendous amount of information about various bike groups online

(the Midnight Ridazz online calendar alone is a treasure trove), but

maybe there's room for a knowledge archive on a movement-wide scale

that would gather stories from many sides of the city.

"Building a Bike Movement in Autopia" is sponsored by the Center for Ethnography and is part of the Bicicultures Roadshow, a mobile conference bringing research on bike cultures, advocacy, and community into one conversation this April.